Europe’s invisible cloud revolution

How Lidl is using Amazon's 2007 playbook to challenge the cloud giants, and what it reveals about European innovation

Virtually every app we use runs on cloud infrastructure. Every website. Every streaming service. Every business tool.

Cloud is the iron beneath our software. The servers, hard drives, and network cables that physically deliver the bits and bytes that keep our businesses running. To consumers cloud is vaguely known as that magical infinite storage bucket for photos and Netflix content, yet for almost all businesses nowadays, cloud is also a critical piece of infrastructure to keep things running. Business processes, customer support, websites, apps, and what not.

This infrastructure works much like our roads and highways. A system of not just roads, but also gas stations, parking lots. A system of servers, storage, networking, CPUs and GPUs. And just like highways, cloud infrastructure requires enormous investment to build and maintain.

For years, we became used to the idea of a handful of US tech giants dominating this infrastructure. They had first-mover advantage. They had scale. They had capital. The strategy was simple: bigger, better, faster. More data centers. More regions. More services. Build infrastructure everywhere so any app can scale instantly anywhere on the planet. And Europe fell behind. It tried to respond through regulation. GDPR, data protection, sovereignty requirements. Important, but not at all sexy. A stick to threaten with, not a carrot.

Enter Lidl. A discount grocery chain.

Lidl’s gamble

In 2018, Schwarz Group, the company that owns Lidl and Kaufland, faced a decision about their cloud infrastructure. They were managing 575,000 employees across 13,700 stores in 33 countries. Mountains of operational data. Customer loyalty programs. Supply chain logistics. Employee records.

The obvious move was AWS, Azure, or Google Cloud. Instead, they decided to build their own.

Why? Partly because US cloud providers operate under US law, creating genuine legal exposure for European companies under GDPR. But also because at their scale, the business case for owning infrastructure made sense. Only a company the size and complexity of Schwarz Group could justify that investment.

They built StackIT. And it worked. And a year ago, in September 2024, they spun it out as a commercial cloud provider, taking a leaf out of Amazon’s 2007 playbook that ultimately let to AWS.

And here’s the thing: it’s working.

SAP signed up. Bayern Munich signed up. The Port of Hamburg signed up. These aren’t startups looking for cheap hosting. These are major organizations choosing StackIT over the US hyperscalers. Amazon also noticed, and responded with a € 7.8 billion investment in “AWS European Sovereign Cloud”.

Now the question isn’t whether this is working (it clearly is). The question is how and what does it mean?

The business case shift

The hardware and software powering the datacenter operations has seen a dramatic leap in commoditisation. Price of ever powerful servers and harddrive storage has continued to come down. And software like OpenStack to manage this hardware has emerged as a reliable backbone for cloud providers.

That shift has changed the business case for data centres. Yes they still require massive amounts of investment, and massive amounts of operational costs. But the numbers are no longer insurmountable, in order to provide a reliable service. That has made it possible for Lidl to build the business case to invest and build StackIT.

And that sheds light on a different strategic consideration; is bigger always better?

Is bigger always better?

StackIT operates data centres only in Germany and Austria (for now). That is a big difference to the Amazon’s and Google’s of the world, selling ‘edge computing’ (servers globally available, instantly serving customers close by).

If you’re a German bank, a Dutch healthcare provider, or a French government agency; do you actually need data centres in Singapore, Sydney and São Paulo? I think not.

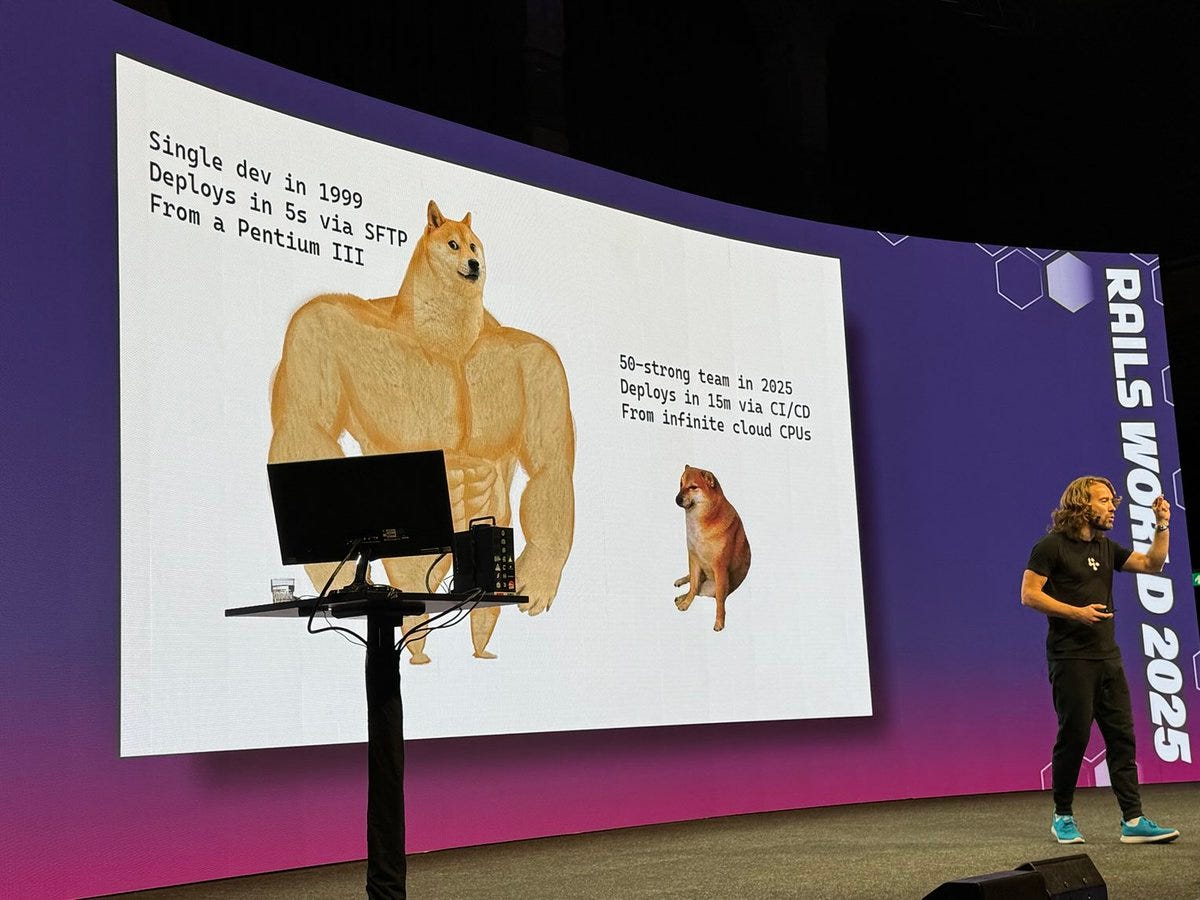

Most European businesses serve primarily European customers. Global distribution is not a feature. It is irrelevant complexity. And that just might turn out to be one of the hyperscaler’s Achilles’ heels. All that cloud scalability brings complexity.

StackIT strikes me as being more down to earth. Asking what do businesses actually need? And since cloud as a concept has become a sort of no-brainer for businesses, the actual requirements for it are also clear. Data in Europe. Full GDPR compliance. Reliable performance. Fair pricing. Good developer tooling. And maybe most importantly; no vendor lock-in. That means that a business with a no-nonsense, down-to-earth value proposition, would actually stand a good chance.

The European pattern

StackIT fits a broader pattern I’ve been noticing.

I see certain European technology companies succeeding by flying completely under the radar. Hetzner, the German hosting company with a developer cult following. Proton Mail, the Swiss email service becoming a serious Gmail alternative. OVH and Scaleway in France. Dozens of European VPS providers. These companies share a philosophy: deliver good service at fair prices. Largely skip the marketing theater (I mean, just look at their websites).

This is a distinctly un-Silicon Valley approach. And I think it just might work for European customers. More down-to-earthness. And it looks to me StackIT is this philosophy at enterprise scale.

StackIT didn’t emerge because some founder had a vision. It emerged because a company faced a real problem (where do we put our data?), built a solution methodically, and realized others had the same problem. And StackIT didn’t succeed because of European regulation. Its value proposition on its own is strong enough. GDPR is just a helping hand in pushing customers to look for European alternatives.

This might be how European innovation actually works: slower to emerge, less hyped, solving genuine problems with sustainable models when real need meets real opportunity.

What I’m watching for

I’m watching whether this represents the beginning of a European cloud resurgence. A rethinking of what we actually need from our servers. And potentially a shift away from the traditional cloud platforms with their lock-in services. A simplification, and re-embracing of good old European servers. Whether running on VPS (virtual private servers), or on larger (EU) cloud providers like StackIT.

And I’m curious to see what other European companies might follow this playbook. What other foundational tech has changed to shift the business cases around. And what other tech can be productised by European businesses, to serve other European businesses.

And I’m watching whether we’re seeing a return to practical, down-to-earth business thinking more broadly. Less “change the world” aspiration, more “solve real problems well at fair prices.”